Domestic Media Interdependence and Beethoven's Third Piano Concerto

I recently watched Phil Grabsky’s feature length documentary In Search of Beethoven. It provides a fascinating overview of Beethoven’s life and incorporates comments and musical performances by many different artists and performers.

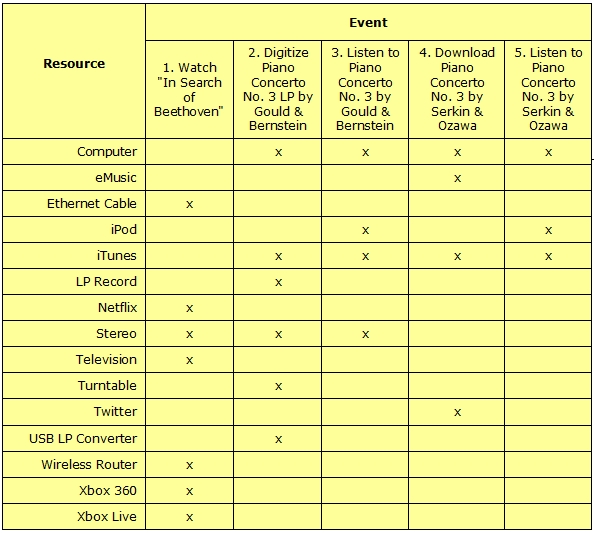

I enjoyed the documentary so much I decided to review my own personal music collection for Beethoven works. I ended up digitizing an old phonograph record I had of Glenn Gould performing the Third Piano Concerto. In the process of doing this I realized how dependent I’ve become on a variety of technologies for accessing music. I decided to look in more detail at the process I followed. The following table is the result.

Table 1. Beethoven Third Piano Concerto and Domestic Media Interdependence

Columns in Table 1 represent the basic sequence of events. Rows represent the different media and technologies I used:

Watch “In Search of Beethoven.” At the end of the day I sat down in front of my living room TV, switched on the TV, stereo, and Xbox, and accessed Netflix. The Xbox is connected to the wireless router via an ethernet cable and also harbors an “Xbox Live” subscription that provides access to Netflix via my Verizon DSL internet sservice, among other things. Flipping through the Netflix choices I chanced across the Beethoven documentary and, on a whim, selected it. I loved it. It got me to wondering which pieces I’d heard in the documentary I had in my own personal music collection.

Digitize Piano Concerto No. 3 LP by Gould & Bernstein. It turns out a had quite a few Beethoven symphonies and quartets but only the Fifth piano concerto loaded into my iTunes. Then I remembered my phonograph record collection that I have been digitizing and, lo and behold, I have an entire boxed set of Beethoven piano concertos played by the legendary Glenn Gould with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra conducted by Leonard Bernstein. I dusted off the record and played it back; very few pops and crackles, so I digitized it using my Ion turntable feeding my E Z Audio Converted software connecting to my laptop computer via a USB cable. I imported the file to iTunes and cleaned up the indexing data.

Listen to Piano Concerto No. 3 by Gould & Bernstein. I listened to the performance several times over the next few days both via the system hooked to my computer and via my iPod Classic and headphones. The surface noise from the old LP was very low level and the sonic fidelity was great. I even got to enjoy the really weird cadenza that Gould supplied. But the more I listened to the work the more dissatisfied I became; the orchestra just didn’t sound very good. While I’m not a musician myself I’ve listened to enough orchestral performances over the years to realize when someone hasn’t rehearsed enough. I resolved to find a better recoding.

Download Piano Concerto No. 3 by Serkin & Ozawa. Enter eMusic the online music service I switched to several years ago to avoid iTunes’ DRM processing. Despite a few hiccups with the rather cumbersome eMusic search engine — which appears not to have been optimized for classical music — I quickly located a large number of Third Piano Concerto performances. I immediately checked the one by the performer in the music documentary but, alas, one of the movements was “album only” and I already owned recordings of other works on the album. Not wanting to duplicate what I already had in my collection I selected another recording that didn’t have a similar restriction, one by Serkin and Ozawa. I used Twitter to express my displeasure with the restrictive eMusic policy. I downloaded the new recording and loaded it into iTunes.

Listen to Piano Concerto No. 3 by Serkin & Ozawa. I’ve listed to the Serkin & Ozawa performance several times now. It’s an older recording but the sonic fidelity and recording quality is very good. The orchestra is far superior to the Gould recording.

Looking at the above table and text what immediately occurs to me is that there are a lot of steps involved, and a lot of different media as well.

In the old days I would just have gone to the store and bought another album. Here, though, I was able to accomplish this via the comfort of my own home. I had the ability to follow up from my viewing of the documentary, I had a recording I could convert to a more convenient format, and via my music subscription service I could locate a better version of what I already had. All this happened in the matter of a few days from listening to the initial documentary to ending up with what I consider to be a high quality recording.

Most interesting to me is the duration of the transactions. Thinking back and setting aside the time spent actually listening to the documentary and to the recorded versions of the concerto, these processes only took a few minutes to locate, download, and process. That’s compared with the time involved in using brick and mortar stores or waiting for the mail to arrive.

Another point: the two resources used most often in the above events are the computer (I’m using a Sony Vaio laptop running Windows 7) and iTunes. Together they combine powerful connectivity, communication, organization, and management functions in a very usable package. Add to this the portability offered by the iPod itself and I realize that, at least in terms of an amateur music appreciator like myself, we indeed live in very good times.

But there are catches. The cost of providing and supporting the infrastructure is not insignificant; there are the Verizon DSL connection, the eMusic subscription, and the Xbox Live subscription to consider. So this “convenience” and immense variety and selection come at a price.

Right now I’m willing to pay that price. But should we ever return to a “rental only” media model — such as being supported by the new AppleTV — there may come a time in the future when there are no older recordings lying around to convert from one format to another, and there may not be the wide selection we have now of all the older works that make up the “backlists” of media retailers. I still like having my own copy of something that I can take anywhere and listen to repeatedly. But the infrastructure to support this, as shown above, is not insignificant.

Copyright (c) 2010 by Dennis D. McDonald. For another example of media interdependence see Using New Media To Sell Old Media.